While MERS has served to illustrate the utter recklessness of the securitization industry, in that its promoters apparently believed that they could implement it nationwide and simply force state law to comply. But as the banks have found out, the law is not always so obliging.

Today, Washington State, which is a non-judical foreclosure state, gave MERS a serious setback. Its finding in Bain v. Metropolitan Mortgage, that MERS may not foreclose in Washington, is not as bad as it sounds, since MERS instructed in servicers to stop foreclosing in its name in 2011. But the reasoning of the ruling is far more damaging. And the court has opened up new grounds for litigation against MERS in Washington, in determining that it false claim to be a beneficiary under a deed of trust is a deception under the state’s Consumer Protection Act (whether that can be proven to have led to injury is a separate matter).

The case came before the Washington Supreme court because it was asked by a Federal district court to address three certifying questions:

The court also took a dim view of the diffused responsibilities within the MERS system:

On the final matter, of whether MERS being an unlawful beneficiary would give rise to claims under the state’s consumer protection laws, the court said it could, depending on the facts of the case:

Perhaps most interesting is that MERS has taken to settling cases where it gets wind the court might rule against it, deliberately skewing the record to create the impression that its procedures and legal structure enjoy more acceptance from courts than they actually do. Given its recent conservatism, I wonder what led them to hazard a high profile loss. It might be that Washington’s deed of trust is distinctive enough that they thought they could take the chance, in that they could take the position that its implications for other states are very limited. We’ll see soon enough if that assumption is valid.

Today, Washington State, which is a non-judical foreclosure state, gave MERS a serious setback. Its finding in Bain v. Metropolitan Mortgage, that MERS may not foreclose in Washington, is not as bad as it sounds, since MERS instructed in servicers to stop foreclosing in its name in 2011. But the reasoning of the ruling is far more damaging. And the court has opened up new grounds for litigation against MERS in Washington, in determining that it false claim to be a beneficiary under a deed of trust is a deception under the state’s Consumer Protection Act (whether that can be proven to have led to injury is a separate matter).

The case came before the Washington Supreme court because it was asked by a Federal district court to address three certifying questions:

Is MERS is a lawful beneficiary with the power to appoint trustees within the deed of trust act if it does not hold the promissory notes secured by the deeds of trust? If no, then:The answer to the overriding question was indeed “no”. The court’s immediate objection was straightforward. MERS claims not merely to be an electronic registry of deeds, but also to be a beneficiary of the deed of trust. However, as the court points out:

What is the legal effect of Mortgage Electronic Registration Systems, Inc., acting as an unlawful beneficiary under the terms of Washington’s Deed of Trust Act? and

Can consumers claim violations of the state’s Consumer Protection Act based on MERS having incorrectly claimed it was a beneficiary of a deed of trust?

Traditionally, the “beneficiary” of a deed of trust is the lender who has loaned money to the homeowner (or other real property owner). The deed of trust protects the lender by giving the lender the power to nominate a trustee and giving that trustee the power to sell the home if the homeowner’s debt is not paid. Lenders, of course, have long been free to sell that secured debt, typically by selling the promissory note signed by the homeowner. Our deed of trust act, chapter 61.24 RCW, recognizes that the beneficiary of a deed of trust at any one time might not be the original lender. The act gives subsequent holders of the debt the benefit of the act by defining “beneficiary” broadly as “the holder of the instrument or document evidencing the obligations secured by the deed of trust.”These days, that “instrument or document evidencing the obligations secured by the deed of trust” is a promissory note, a borrower IOU. But MERS executives have said consistently in depositions that MERS has nothing to do with the borrower notes. So under Washington law, it can’t be the beneficiary of the deed of trust and hence can’t foreclose.

The court also rejected the idea that MERS could act as an agent of the lender/noteholder:As an aside, the funniest bit of MERS’s argument was a dressed up “deadbeat borrower” pleading:

But Moss also observed that “[w]e have repeatedly held that a prerequisite of an agency is control of the agent by the principal.” Id. at 402 (emphasis added) (citing McCarty v. King County Med. Serv. Corp., 26 Wn.2d 660, 175 P.2d 653 (1946)). While we have no reason to doubt that the lenders and their assigns control MERS, agency requires a specific principal that is accountable for the acts of its agent. If MERS is an agent, its principals in the two cases before us remain unidentified.12 MERS attempts to sidestep this portion of traditional agency law by pointing to the language in the deeds of trust that describe MERS as “acting solely as a nominee for Lender and Lender’s successors and assigns.” Doc. 131-2, at 2 (Bain deed of trust); Doc. 9-1, at 3 (Selkowitz deed of trust.); e.g., Resp. Br. of MERS at 30 (Bain). But MERS offers no authority for the implicit proposition that the lender’s nomination of MERS as a nominee rises to an agency relationship with successor noteholders.13 MERS fails to identify the entities that control and are accountable for its actions. It has not established that it is an agent for a lawful principal.

MERS argues, strenuously, that as a matter of public policy it should be allowed to act as the beneficiary of a deed of trust because “the Legislature certainly did not intend for home loans in the State of Washington to become unsecured, or to allow defaulting home loan borrowers to avoid non-judicial foreclosure, through manipulation of the defined terms in the [deed of trust] Act.”The court was not moved and basically said it was the banks’ fault if they got themselves in the position of not being able to foreclose:

One difficulty is that it is not the plaintiffs that manipulated the terms of the act: it was whoever drafted the forms used in these cases.But the ruling goes further and picks at the foundations of the MERS system, and not just its role in foreclosures. Most state hew to the view of the 1867 Supreme Court decision, Carpenter v. Longan, that the mortgage cannot be separated from the note, that the mortgage is a “mere accessory” of the note and has to travel with it. The Washington Supreme court focuses on the fact that MERS inserts a new party:

As MERS itself acknowledges, its system changes “a traditional three party deed of trust [into] a four party deed of trust, wherein MERS would act as the contractually agreed upon beneficiary for the lender and its successors and assigns.” MERS Resp. Br. at 20 (Bain). As recently as 2004, learned commentators William Stoebuck and John Weaver could confidently write that “[a] general axiom of mortgage law is that obligation and mortgage cannot be split, meaning that the person who can foreclose the mortgage must be the one to whom the obligation is due.”The court later states that it is not clear whether MERS split the note and the mortgage; if MERS really is the agent for the noteholder, it is likely no separation occurred.

The court also took a dim view of the diffused responsibilities within the MERS system:

While not before us, we note that this is the nub of this and similar litigation and has caused great concern about possible errors in foreclosures, misrepresentation, and fraud. Under the MERS system, questions of authority and accountability arise, and determining who has authority to negotiate loan modifications and who is accountable for misrepresentation and fraud becomes extraordinarily difficult. The MERS system may be inconsistent with our second objective when interpreting the deed of trust act: that “the process should provide an adequate opportunity for interested parties to prevent wrongful foreclosure.”The Supreme Court effectively punted on the second question, which was what would be the legal effect of MERS being an unlawful beneficiary under the state’s Deed of Trust Act: “…resolution of the question before us depends on what actually occurred with the loans before us and that evidence is not in the record.”

On the final matter, of whether MERS being an unlawful beneficiary would give rise to claims under the state’s consumer protection laws, the court said it could, depending on the facts of the case:

…we answer the question with a qualified “yes,” depending on whether the homeowner can produce evidence on each element required to prove a CPA claim. The fact that MERS claims to be a beneficiary, when under a plain reading of the statute it was not, presumptively meets the deception element of a CPA action.The Seattle Times amusingly quoted the MERS attorney complaining that the court respected the law:

Douglas Davies, the local attorney who represented MERS, said the court imposed “the literal language of a dated statute,” reaching a decision that didn’t benefit either borrowers or lenders.Funny, the state attorney general apparently didn’t think so, since he wrote a brief supporting the borrower.

“The Supreme Court has created a chaotic situation and essentially left it to a taxed legislature to come up with a solution,” Davies said in an e-mail late Thursday. “The only certainty that will come from this decision is a plethora of lawsuits that will overburden an already burden[ed] judicial system.”

Perhaps most interesting is that MERS has taken to settling cases where it gets wind the court might rule against it, deliberately skewing the record to create the impression that its procedures and legal structure enjoy more acceptance from courts than they actually do. Given its recent conservatism, I wonder what led them to hazard a high profile loss. It might be that Washington’s deed of trust is distinctive enough that they thought they could take the chance, in that they could take the position that its implications for other states are very limited. We’ll see soon enough if that assumption is valid.

How to Beat Vulture Debt Collectors

In a bit of synchronicity, last weekend I had dinner with a buddy whose sibling recently was dunned by a buyer of junk debt. For those not familiar with this dark underbelly of the credit markets, these vultures buy consumer debt from banks (mainly credit card receivables) that the bank

has written off. That means they don’t think it’s worth pursuing. At best it’s too close to the statute of limitations expiring or the documentation is questionable or the amounts are all wrong. Most of the time. it’s worse than that: the debt was never owed (they are going after the wrong person), the debt was paid off or discharged in bankruptcy, the statute of limitations has long passed.

The buyers of this debt pay pennies on the dollar and treat it like a lottery ticket. They sue, but have NO intention of spending any money on the case beyond making that filing. Their fond hope is that the borrower fails to respond, and they win a default judgment. With that in hand, they can garnish wages or bank accounts.

The flip side is any minimal credible response will beat back these claims. And remember, the burden of proof is on the debt collector to demonstrate that the consumer agreed to the debt, to provide a full record of principal, interest, payments, and fees, and to prove a complete and unbroken chain of title (sound familiar?).

An article by law professor Peter Holland is a superb guide on how to beat these cases. While the intended audience for this article is lawyers, it is highly accessible, and gives a sense of what an utter swampland this area is. He also stresses that it takes diligence rather than experience to pursue these cases:

Nathalie Martin of Credit Slips recounts some of the recommendations Holland makes:

Holland concludes:

The buyers of this debt pay pennies on the dollar and treat it like a lottery ticket. They sue, but have NO intention of spending any money on the case beyond making that filing. Their fond hope is that the borrower fails to respond, and they win a default judgment. With that in hand, they can garnish wages or bank accounts.

The flip side is any minimal credible response will beat back these claims. And remember, the burden of proof is on the debt collector to demonstrate that the consumer agreed to the debt, to provide a full record of principal, interest, payments, and fees, and to prove a complete and unbroken chain of title (sound familiar?).

An article by law professor Peter Holland is a superb guide on how to beat these cases. While the intended audience for this article is lawyers, it is highly accessible, and gives a sense of what an utter swampland this area is. He also stresses that it takes diligence rather than experience to pursue these cases:

Revealing the defects in these documents does not require a deep background in consumer law. It just requires a cup of coffee, your undivided attention, a yellow highlighter, and a red pen.The article warns, however, that fewer than 1% of the consumers who respond in court are represented by counsel, and that they are typically not treated equitably, since debt collectors have convinced many judges that borrowers are deadbeats and that the rules of evidence don’t hold in small claims (as the article stresses, that is not accurate). Holland does not intend his article to be a guide to pro se defendants, but it can serve as a great guide for newbie lawyers or even law students to take on these cases. And he also points out that in the wake of the robo-signing scandal, many judges are more sensitive to assaults on the integrity of the courts than they once were, and it’s not difficult to depict some of the issues presented by these actions as being similar to those in robosigning cases.

Nathalie Martin of Credit Slips recounts some of the recommendations Holland makes:

1. Read the complaint and supporting documents very carefully. Is the named plaintiff the same party named in the documents supporting the debt? Is there any chain of title tying the plaintiff to the debt? Is the debt collector licensed in your state? Is the contract for the debt even attached to the complaint? How is the debt supported by evidence? If there is some document attached to prove the debt, can you read it? Was it generated after the fact? By whom? Has the statute of limitations run?And there’s lots more, like investigating whether the plaintiff had a checkered history (felons on staff? violations of the Fair Debt Collections Practices Act? FTC fines? evidence of past use of fraudulent affidavits?) and putting the judge on notice of any findings.

2. Know the elements of an “account stated” cause of action. These include the establishment of a debtor-credit relationship, an agreement by the debtor and creditor as to the amount due, and an agreement by the debtor to pay the amount allegedly due.

3. Carefully scrutinize the affidavit. Here comes the fun. Google your affiant. Many people who have signed these affidavits have admitted under oath to singing thousands of these in one day, and many have signatures on Google that will not match the ones in your affidavit. Look at your state’s affidavit rules. Of course these rules will require affiants to have personal knowledge and likely yours will likely not qualify as evidence. If the affidavit says this is true “to the best of my knowledge” the affiant is admitting to not knowing the real facts and the affidavit can be stricken from the evidence.

4. Master the relevant rules of evidence. No personal knowledge, no recovery. No proof of debt, no recovery.

5. Tell the judge why this matters. Many of these debtors do not owe these debts.

Holland concludes:

Allowing debt buyers to run roughshod over consumers and the courts is a denial of due process. It enriched junk-debt buyers at the expense of consumers, legitimate creditors, and our judicial system…Trying and winning these cases will have the systemic impact of helping restore a sense of justice and fairness which lies trapped beneath the heavy weight of the junk-debt buyer.Amen.

Spain Out of Options

Yves here. We’ve flagged in earlier posts how the Spanish banking

crisis has the potential to become destabilizing politically, as if Spain wasn’t already at considerable risk of upheaval. Spanish depositors were pushed to convert their deposits into preference shares, which they were told were just as safe. This was a simple desperation move by the banks to save their own skins, customers be damned, by raising equity from the most unsophisticated source to which they had access. And now that that gambit failed, these shareholders are due to have those investments wiped out unless the Spanish authorities can cut a deal to spare them. Don’t hold your breath.

By Delusional Economics, who is horrified at the state of economic commentary in Australia and is determined to cleanse the daily flow of vested interests propaganda to produce a balanced counterpoint. Cross posted from MacroBusiness

I mentioned back in early July that Spain had a serious political problem brewing because the draft Memorandum of Understanding for the Spanish banking system clearly stated that:

Although there are other factors involved, I think this is one of the primary reasons Mariano Rajoy has been so hesitant to move forward with any bailout, and it comes as no surprise that he is now attempting to negotiate a way out for these people:

By Delusional Economics, who is horrified at the state of economic commentary in Australia and is determined to cleanse the daily flow of vested interests propaganda to produce a balanced counterpoint. Cross posted from MacroBusiness

I mentioned back in early July that Spain had a serious political problem brewing because the draft Memorandum of Understanding for the Spanish banking system clearly stated that:

Banks and their shareholders will take losses before State aid measures are granted and ensure loss absorption of equity and hybrid capital instruments to the full extent possible.From a market perspective this is absolutely the correct thing to do. Equity is a risky business. You take a punt, the banks falls over, your money it gone, fair enough. But in Spain it’s not that simple because of something I commented on in April:

The key in a banking crisis is to keep the confidence of depositors. But while many countries relied on capital injections and government guarantees, Spanish banks have added a unique twist of effectively turning some depositors into equity holders. That puts customers on the front line.And so now, under the watchful eye of the Spanish regulators, depositors in Spanish banks had been converted into equity holders and these same people were about to see their savings eaten up by the first stages of a banking bailout.

Some banks started by persuading depositors to switch from low, interest-bearing accounts into preference shares, which paid a fixed, higher interest rate. The benefit for the banks was that these securities counted as core capital under banking rules. UBS says Spanish banks issued €32 billion ($42.7 billion) of such instruments from 2007 to 2010.

But as the crisis deepened, these instruments became illiquid, trading at deep discounts. At the same time, they ceased to count as core capital under new rules known as Basel III. So banks have encouraged investors to convert preference shares into either common stock or mandatory convertible notes, which pay a high initial yield before later converting into stock.

Although there are other factors involved, I think this is one of the primary reasons Mariano Rajoy has been so hesitant to move forward with any bailout, and it comes as no surprise that he is now attempting to negotiate a way out for these people:

The Spanish government is in talks with Brussels to allow tens of thousands of retail clients who bought risky savings products from now nationalized lenders to avoid losing their investments as part of Spain’s bank bailout.Apart from the obvious question of whether they will actually get a deal, the other question is will the banks be in any position to make those payments in the future. As WSJ reports, the banking system looks increasingly flakey as deposits continue to leave the country and the hole is filled by ECB:

In place of inflicting large losses on small savers who purchased savings products linked to preference shares in in the lenders known as cajas, the Spanish government is negotiating a compromise where they will suffer an instant haircut, and then be repaid in full over time by their banks, people familiar with the talks said.

The decision to inflict losses on holders of high interest preference shares and subordinated debt in rescued savings banks has been highly controversial in Spain, with the terms of the country’s bank rescue not distinguishing between professional and retail investors.

Spanish banks borrowed a record amount from the European Central Bank in July, as other sources of funding evaporated further in the weeks following the announcement of a €100 billion ($123 billion) bailout for the country’s financial industry.And the latest report from Tinsa makes it very clear that the bubble’s deflation is far from over:

Bank of Spain data indicated that net ECB borrowing rose to €375.55 billion from €337.21 billion in June. It was the 10th straight month of increases, highlighting how the country’s lenders are having more and more difficulty financing themselves through private investors.

Spain’s traditional funding sources have been dwindling as the economy sinks deeper into a downturn. During the Spanish construction boom of the past decade, German and other European banks were more than willing to fund the rapid expansion of the Spanish banking system, inflating the country’s credit bubble.

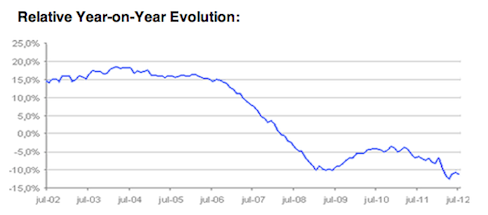

The IMIE General index registered a year-on-year decline of 11.2% in July, pushing the index down to 1577 points. The cumulative decline in house prices since the market peaked in December 2007 is 31%.

…

In terms of the cumulative decline in house prices by region since peak prices, there was a 37.2% fall in July for the “Mediterranean Coast”; followed by 33.5% for “Capitals and Major Cities”, 32.1% for “Metropolitan Areas”, 29.2% for the “Balearic and Canary Islands” and 25.9% for “Other Municipalities”, which comprises the remainder.

Mariano Rajoy is expected to meet Herman Van Rompuy, Angela Merkel, Mario Monti and Finland’s President, Sauli Niinistoe, over the next few weeks in order to discuss his country’s future. It is, however, increasingly obvious that he will have little choice to accept whatever he is given, and I have to question again exactly how long he has left in politics.

Moe Tkacik: Student Debt – The Unconstitutional 40 Year War on Students

Yves here. I’m featuring this post not simply because the student debt issue is coming to serve as a form of debt servitude, but also because the backstory is so ugly. Student debt is the only form of consumer lending where the obligation cannot be discharged in bankruptcy. This story chronicles how persistent bank lobbying, including disinformation portraying student borrowers as likely deadbeats, led to increasingly draconian treatment of student loans. A second reason for posting it is that due to technical difficulties at Reuters, the original ran without the hyperlinks, which are of interest to serious readers.

By Moe Tkacik, a Brooklyn-based journalist who writes at Das Krapital. First published at Reuters.

You don’t have to take it from me: a preeminent bankruptcy scholar made precisely this argument under oath before Congress. In December 1975, when Congress was debating the first law that made student loans non-dischargeable in bankruptcy, University of Connecticut law professor Philip Shuchman testified that students “should not be singled out for special and discriminatory treatment,” adding that the idea gave him “the further very literal feeling that this is almost a denial of their right to equal protection of the laws.”

By Moe Tkacik, a Brooklyn-based journalist who writes at Das Krapital. First published at Reuters.

Lobbyists' trillion dollar revenge on nerds

You have probably mentally catalogued the student loan crisis alongside all the other looming trillion dollar crises busy imperiling civilization for the purpose of enriching the already rich. But it is different from those crises in a few significant ways, starting with the fact that the entire student loan business is arguably unconstitutional.You don’t have to take it from me: a preeminent bankruptcy scholar made precisely this argument under oath before Congress. In December 1975, when Congress was debating the first law that made student loans non-dischargeable in bankruptcy, University of Connecticut law professor Philip Shuchman testified that students “should not be singled out for special and discriminatory treatment,” adding that the idea gave him “the further very literal feeling that this is almost a denial of their right to equal protection of the laws.”